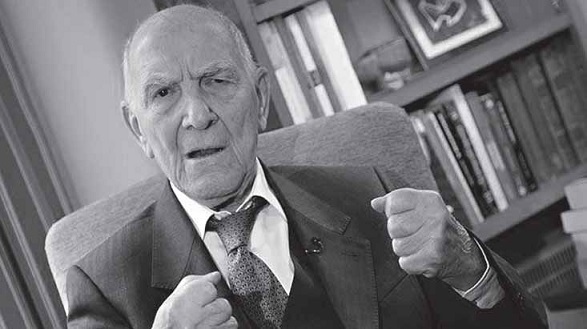

Stéphane Hessel: The rebellious diplomat (1917-2013)

abracad, · Categories: externally authored, spiritual politicsby Jeannette Schneider

The author of the internationally popular pamphlet Indignez-vous! (translated as Time For Outrage), Stephane Hessel spent his life warning of the dangers of "the unbearable dominance of market forces".

Stéphane Hessel, the grand old man of 'the call for social outrage' died on 23 February 2013 at the age of 95. His pamphlet Indignez-vous! (the English title is: "Time for Outrage") was published in 2010 and originally aimed at the French, especially the youth. To his delight and surprise, within a short time, 2 million copies were sold in his own country. By now 4.5 million copies have been sold in 35 countries. In Spain 'Los Indignados' took their name from the title of Hessel's book, and the Occupy movement was inspired by it. Later Hessel published an additional three books all about the need for social and political change.

Stéphane Hessel, the grand old man of 'the call for social outrage'.

Why did his voice resonate so widely? First of all, as he himself stated, it had much to do with his long life and experience. But there is more: the simplicity of his words, their spontaneity, the straightforward way he spoke and above all, the fact he had touched a sore spot - we all know that many things are very wrong today. We are fortunate that someone of his calibre dared to speak out in clear language about what is wrong with our society.  Â

Hessel had the authority to make us listen. Born in Berlin, he moved with his family to Paris in 1924 (he became a naturalised French citizen in 1939). After studying philosophy he served in the French army during the Second World War; he was captured in 1941, fled to England, returned in 1944 and joined the French Resistance, was caught and transported to Buchenwald where he awaited execution. He was wily enough to be able to seize an opportunity to escape and in so doing, escaped death. He worked under another name in German factories, escaped again, was captured and finally succeeded in fleeing to the Allies. In 1946 he entered diplomatic service for the French government; and in New York, from 1946 to 1949 he was a member of the Commission for Human Rights of the United Nations, helping to produce the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. He later represented France in various diplomatic and political functions, remaining true to his old ideals.  Â

There, in a nutshell, we see the spirit of Stéphane Hessel: a diplomat unable to bear injustice and not afraid to express his opinions. His formidable career adds extra weight to his words. Despite experiencing danger and disaster, he was able to maintain his balance.

Indignez-vous!

Although Hessel centres his argument in Indignez-vous! on France, most of it is applicable to the rest of the world. His universality explains the enormous success of his writings. He admits that even though he is optimistic by nature, he sometimes feels sad that his fight after the Second World War for the nationalisation of industries, the state control of public utilities and human rights has been neglected in recent years.  Â

As point of departure for expanding on his views, Hessel cites the Programme of Le Conseil National de la Résistance from 1944, meant to be the foundation for a free democracy in France once the war was over. To summarise: social security and a pension for everybody and the nationalisation of electricity and gas, coal mines, insurance companies and banks; the restitution to the people of the big monopolised means of production, the result of collective labour. The collective should take precedence over the private: the just sharing of the world's riches worked for by the people, needed to be placed above the power of finance. However, in 2013, we see an ever-growing gap between rich and poor. Another stated goal of the 1944 Programme: a real democracy needs a free press independent of the State and of the power of money or exterior influences. Hessel comments that the independence of the media is in danger these days. The Resistance demanded education for all French children, without exception or discrimination. In 2008 the measures taken by the French government undermine this ideal.  Â

Throughout his life he stood firm for these principles but it is now, in our times, that he thought it was time to raise his voice about what he saw happening: the gradual destruction of all he stood and had fought for. National governments for instance, say they can no longer afford such social security programmes. It is obvious that this is not the case. Since 1945, when Europe lay in ruins, enormous amounts of wealth have been generated. But now it is the power of the financial world which prevails - described by Hessel as "the unbearable dominance of market forces". The privatised banks are currently awarding their top managers and shareholders excessively large dividends and salaries without any concern for the collective good.   Â

The basis of the French Resistance was active outrage. Hessel calls on the young in particular to take inspiration from the veterans of the wartime Resistance. He admits that then it was easier than today to act in unison because the issues were more easily defined: the Nazi occupation and, a decade later, the struggle for decolonisation. To Hessel the modern world is far more complex now since the planet itself is in danger, something no one could have imagined some 70 years ago. This is all the more reason to be both outraged and committed. He cites Sartre: "Everyone is responsible as an individual," that is, without reference to any power outside of the self. The worst possible attitude is indifference; passionate commitment is, after all, an essential human quality which confers the power to resist.  Â

Outrage is essential because our dignity is being threatened, and dignity is the crucial concept in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As Hessel says in Tous comptes faits: "Violation of dignity is unacceptable," stressing the universality of the Declaration. It is a matter of ethics not morals, because morality is connected with convention and modes of conduct which differ in different parts of the world, while ethics is about the right action at the right moment. Proper action implies inherent dignity and justice, influenced by the person taking action and the situation in question. Consider the concept of Dharma in Hinduism. So outrage is the first step in rejecting what is unacceptable. However, indignation as an emotion can be unhealthy (Spinoza), but if kept under control by reason it can lead to the desired result. It requires collective consciousness, followed by creative and innovative steps to develop ideas from which the will to change follows automatically.  Â

Hessel's 29-page pamphlet is a wake-up call from lethargy and dejection to belief in the possibility of change. It calls for commitment, active involvement without violence. Hessel explains, however, that it is usually wishful thinking to expect immediate results, and that some failure is inevitable and perseverance is required. Hope is involved, Hessel admits, and the path from words to deeds is difficult. Nevertheless, he remains optimistic and hopes his message will inspire people to action. He cites several episodes in history when an improbable situation was reversed and became reality, when what seemed utopian was realized, by our own actions, not by looking to some outside transcendental force. Nor by revolution, which would destroy the treasures of the past. On the contrary, change comes through metamorphosis, which keeps identity intact, and transforms it into something new. As he concludes inIndignez-vous!:Â "To create is to resist. To resist is to create."Â

source: © Share International

See also:

Filed in: externally authored, spiritual politics

Leave a Reply