The people and the planet

abracad, · Categories: environment, externally authoredInterview with Stephen Leahy

by Felicity Eliot

Canadian environmental journalist Stephen Leahy discusses the obstacles to halting climate change and the exploitation of resources in emerging countries.

Stephen Leahy has worked as a freelance Canadian journalist for the past 12 years, including five years writing for Inter Press Service. Leahy specialises in science, the environment and agriculture. He has been published in leading magazines and newspapers in several countries. Based near Toronto, Canada, Leahy is a professional member of the Society of Environmental Journalists. He is also the 2012 co-winner of the Prince Albert/United Nations Global Prize for Climate Change.

Stephen Leahy

Share International has recently featured two of Leahy's articles 'Climate inaction is a clear failure of democracy' (January/February 2013) and 'Weird, and getting weirder' (March 2013). Felicity Eliot interviewed him via Skype for Share International.

Share International: You've been an environmental journalist and activist for more than a decade; what concerns you most when you look at the state of our planet now?

Stephen Leahy: I think I would say straight away that we're going in the wrong direction with many of our activities. For instance, the way in which we set up our economies.

SI: So you link economics and environment?

SL: Yes. This idea of endless growth is clearly a fallacy.

SI: To many the notion of growth is essential. You don't see it that way?

SL: No, it's clearly impossible. And now we're running up against the limits of the planet to sustain us. We're moving into dangerous times.

SI: Could you please say more about why you reject the idea of growth?Â

SL: Constant material growth in a finite system - which our planet is - is quite obviously not feasible.

Conversation turned to President Obama's second inaugural speech, which placed a fair amount of emphasis on environmental issues and ensuring a sustainable future. Stephen Leahy remarked that Obama's speech indicated at least an intention to do more to protect the planet but that the President's hands are tied by other elected representatives.

SL: I believe, and have said so many times, without a push from the public - meaning tens of thousands of people on the streets and in front of the White House demanding change and demanding action on climate change - it's not going to happen.

SI: I remember that in one of your articles you quoted Pat Mooney (executive director of the Action Group on Erosion, Technology and Concentration (ETC) Group, an international environmental organisation based in Ottawa) who said that "governments, the media and the public aren't paying attention to the 'planetary emergency' unfolding around them. The situation is like firefighters yelling 'fire' in a crowded room and still no one listens." It's clear, too, that the general media and world leaders, even now, are paying scant attention. So, you see people power as being an important lever?

SL: Yes, I think that's what going to be necessary to make the changes. I suppose it's like the civil rights movement in that it took hundreds of thousands of people out on the streets. Now it's so obvious, you wonder why it took so long - why didn't they make the needed changes back in the 1960s? But it took an enormous effort on the part of the public to achieve their goal.

SI: I'd like to ask you about how we, the people, can make our influence felt in the big powerful lobbies - the vested interests?

SL: Well, organising mass protests is certainly one step, one way of doing it. But there are also other ways, for example, people deciding not to use some of the products. This is already happening, of course. Or people going out of their way to block the production or sourcing of certain products. People surround coal plants to disrupt or prevent mining in order to protect the local environment. Or block railway lines that are transporting coal. I think there's going to be a lot more of that kind of action - this year and in the years to come.

SI: Could we look in detail at the problem of carbon emissions? Could you explain why this is such a crucial issue? I know you've said: "The most important number in history is now the annual measure of carbon emissions."

SL: What's driving climate change are the emissions from the use of fossil fuels. The more emissions, the more CO2; the more CO2 in the atmosphere the warmer the climate gets. It's pretty simple science, really. In order to keep temperatures from getting much higher you have to reduce the amount of fossil fuels that are getting into the atmosphere. And eventually, we have to stop putting them into the atmosphere entirely. Because we'll have reached a level … we'll have filled up the bath-tub, so to speak.

SI: Do you mean it will become irreversible at some point?

SL: Yes. But what a lot of people don't seem to realize about burning fossil fuels and about CO2 emissions is that they stay in the atmosphere for a long time - for hundreds if not for thousands of years. So, in effect, they're permanent. So when, for example, you drive your car the emissions from the exhaust pipe are going to stay in the atmosphere for hundreds if not thousands of years.

SI: Perhaps we could look at the effects of carbon emissions: obviously emissions and other pollutants are impacting everything - the air, the soil, the seas, water supplies and so on. What should activists and/or ordinary citizens tackle first? Should we all just start taking action on whatever lies closest to our hearts?

SL: Well, at a local level - and maybe this is where the main action will happen first and perhaps it's the most important level - where people can get together locally and figure out ways to reduce the level of carbon emissions collectively in their areas.

There's the very exciting Transition Town Movement where communities get together to seek collective solutions. 'How can we, as a community, cut our emissions and help support our community at the same time? How can we create thriving neighbourhoods and protect them; perhaps protect our own water supplies, grow our own food?' There are more than a thousand of such Transition Towns around the world now, all engaged in this way. And, by all accounts, people find that they really enjoy working together to solve some of these problems.

SI: As activism develops and the voice of the people gets louder and louder you have a lot of power building up against the vested interests. Our political system is part of the problem, isn't it? How to influence the politicians is another problem we're going to have to tackle, wouldn't you agree?Â

SL: Yes. Depending on the country, each has its own problems depending on the political system. But, the fact that we're not doing enough to tackle climate change is a clear indication of a failure of democracy. This is a near and pressing problem that's going to affect everyone on the planet and yet the political leadership are not dealing with it. No one wants to pass on to their children a planet that's at real risk of being unable to support people. So there's clearly a democratic deficit there.

SI: So, participation in the political process is very important?Â

SL: Right. So, what can people do about it? From these community groups, like the Transition Towns, there are representatives who represent the real wishes of the people. One problem is that politics has become very professionalised and most people aren't directly involved anymore. But again, through community efforts people get to experience how important it is to work together and that is the first step towards moving into the political process.

SI: In one of your articles you talk about certain countries moving ahead in how they tackle climate change. I read for instance that [South] Korea is one of those countries. Could you give some examples?Â

SL: Korea has understood that the 21st century is going to belong to those countries that are successful in moving into a low carbon economy, in other words, those countries that understand that the less energy they use, the more successful they will be. In Korea, there are cities - each city is competing with others to see which can be the greenest. So they are really transforming their society quite quickly. Korea and some other emerging economies are really eager for change whereas western industrialised countries - like the UK, Canada, the USA, are not that interested. In fact, they are complacent.

SI: There's another issue I'd like to raise: that of the exploitation of resources in emerging countries and a related problem - land grabs.

SL: It's a big issue in Africa, South America, and some Asian countries too. There's a perception of scarcity - industries are running out of the raw materials and minerals they need. The other thing that's going on is 'markets at play'. Believe it or not but agricultural land has become a very hot commodity in the financial centres of the world. And it is being viewed like a resource - gold, or other rare metals. And as a resource it's being thrown onto the speculative markets, which is of course a very big problem because it's easy for some investment company to throw millions of dollars into some piece of land.

SI: This is a very dangerous situation isn't it?

SL: Yes, it is. It's dangerous because right now we have a billion or more hungry people and when their lands are being tied up by investors in New York or London stock markets they can't possibly compete and they end up losing out. Governments are going to have to be very careful. But, on the other hand, for many countries it's easy cash; they give a lease on the land for 50 years and earn billions.

SI: Yes, but where does the money go? It doesn't go to the small farmers does it?

SL: No. It doesn't and the upshot is more people moving into cities, the growth of slums, informal settlements.

SI: More people starving and increased food insecurity.

SL: It is definitely a bad trend and that's without even considering the climate change impact. Climate change is being felt at the agricultural level first. That's where the biggest impact is going to be, because farmers depend on the weather being relatively consistent year to year. One of the signs of climate change is extreme weather; and extreme weather is very bad for food production.

SI: What do the statistics tell us about the state of the planet and the climate? Has this decade been the warmest?

SL: This has been the warmest decade in recorded history and it's certainly been a time with the most records set: the hottest, wettest, driest - you name it. What's really important to note is that year on year now we have more records than the year before. Here's a statistic I wrote about just this morning: 'If you're 27 years old, or younger, you have never not experienced a warmer than average month - anywhere on the planet. It's been warmer than average for the last 27 years.' (Except for May this year!) It's unprecedented. The planet is warming up; over the last 330 months each month has been warmer than the average.

SI: I noticed that in one of your articles you said that Hurricane Sandy helped President Obama get re-elected.

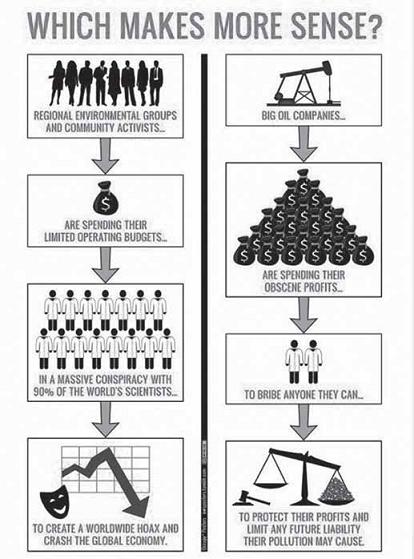

SL: The irony is, a few years ago I asked one of the leading American climatologists at Stanford University, 'What's it going to take for the US to get serious about climate change?' And he told me, 'It'll take a hurricane over New York City, and Washington DC, and Los Angeles, preferably all at the same time in order to wake up Americans and their leaders to the threat of climate change.' But, there's a very large disinformation campaign by the fossil fuel interests who will try to distract people.

SI: This is why an independent media, and independent journalists like you are so important.

SL: The New York Times had nine journalists dedicated to covering environmental issues; they've just closed that department down; it's been disbanded.

SI: How about the future, are you hopeful? Aren't we running out of time?

SL: Hopeful? It depends on the day! And yes, we're running out of time. There are only a few years left for us to peak emissions then reverse their impact. But I do see a lot of dedicated people, especially young people involved in these issues. They're not afraid of change and, of course, they're inheriting the future. They're willing to make changes and a lot of countries want change. We need to build momentum. We need to find ways of reducing our energy needs; and we need to improve our energy efficiency instead of being so wasteful. There are all sorts of solutions; small-scale improved technologies for example, help save energy usage. Europe used to be more energy efficient because of better laws and regulations but the trend is towards more electronics, more stuff. We'll need to make life-style changes. Some people think that less stuff is hard but actually it makes for a better life, a better quality of life. You find other ways to enjoy yourself: to be with other people, to build relationships and be more creative. One problem I think we're all having is envisaging alternative futures. We aren't very good at articulating what we do want. We need artists and poets and filmmakers to help us see new ways forward, to see a vision of the future.

Stephen Leahy is an independent environmental journalist. For more information on how to help independent, community-supported journalism visit his website:Â stephenleahy.net

Stephen Leahy's articles have been collected in two eBooks: Oil Stains in the Boreal Forest: The Environmental cost of Canada's Oil Sands and Steve's Hurricane Handbook 2007.Â

source: © Share International

See also:

Filed in: environment, externally authored

Leave a Reply