"Glaciers are the canary in the global coal mine"

abracad, · Categories: environment, externally authoredInterview with James Balog

by Jason Francis

James Balog, founder of the Extreme Ice Survey, discusses climate change as evidenced by the massive systemic changes wrought by humans in the basic chemistry of the planet. April 2013; source: © Share International

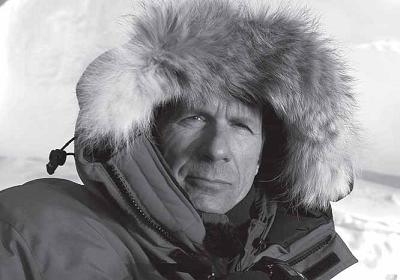

James Balog has been a leader in photographing, understanding and interpreting the natural environment for three decades. He has a graduate degree in geography and geomorphology and is an avid mountaineer. To reveal the impact of climate change, Balog in 2007 founded the Extreme Ice Survey (EIS), the most wide-ranging, ground-based, photographic study of glaciers ever conducted. The project is featured in the highly acclaimed documentary Chasing Ice, which has won numerous awards worldwide. Balog is also the author of eight books; his most recent, Ice: Portraits of Vanishing Glaciers, was released in the fall of 2012. Jason Francis interviewed James Balog for Share International.

From skeptic to advocate

Share International: What prompted you to document the world's changing climate when you were initially a climate change skeptic?James Balog: I was a skeptic because I thought the science was based on computer models. I thought perhaps the issue was being trumped up as an activist cause. And, thirdly, it had not occurred to me that humans were perhaps capable of changing the basic chemistry and physics of this planet. I know this subject area pretty well, but at the time, 15 or 20 years ago, the idea of massive systemic anthropogenic change was not really commonly understood. And I did not understand it.

So I took the time to study the record of ancient climate that was preserved in the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica. I realized that in fact there was empirical evidence of how the climates had changed over time and how different today's climate is compared to how it naturally should be. Once I saw that there was a precise, tangible and empirical record of climate in the ice sheets, I understood that a lot of my previous knee-jerk skepticism was wrong and this was not about computer models. In fact, humans were changing the basic chemistry of the planet and I needed to revise my thinking. That was in the late 1990s. Then I was trolling around trying to figure out how I, as an environmentally concerned photographer, would make a photographic study of this subject. And I kept coming back to the ice. I couldn't see any other way to do it but the ice.

I got a call from the New Yorker magazine one day and they gave me an assignment in Iceland. I had the chance to turn that into aNational Geographic assignment that suddenly got a lot bigger. That all led to the Extreme Ice Survey, and the rest is history.

James Balog

SI: What techniques depicted in your documentary Chasing Ice, do the Extreme Ice Survey use to document the world's vanishing glaciers?Â

JB: The film is a cinematic study of what my team and I have been doing in this project called the Extreme Ice Survey. EIS is a multi-continental study of how the ice is retreating as a consequence of climate change. We have time-lapse cameras deployed in Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Iceland and in Nepal by Mount Everest. These cameras are photographing every 20, 30 or 60 minutes, making a record of how the landscape is changing.

The film team started their coverage right at the beginning of the project and they followed us for about two-and-a-half or three years in the field. They watched what we were doing and made a record of the various adventure, technical and human dramas that were part of this. The film digs into the back-story behind the people and the experiences, and to some degree into my family and how this affected my family life and health. It makes the drama of the team and its story and the glaciers come alive. The main characters are the glaciers, the landscape, but they work in tandem with the human story. It's been a combination of the landscape story and the human story that a lot of people find pretty compelling.

SI: How many locations has Extreme Ice Survey gone to in order to document receding glacial ice?

JB: The glaciers are scattered in the high mountains and the polar regions as well. We can only check in on a few locations. I am not purporting to be making an exhaustive encyclopedic study of the behavior of all the regions of the world, let alone all the glaciers. But the visualizations we are creating are built on the back of the massive scientific record that has been compiled by researchers from all around the world, from on-the-ground and satellite observations. It's very well understood that in the vast majority of places outside east Antarctica, glaciers are retreating. There is a little bit of glacier advance in the Karakoram Range of Pakistan and in mountain ranges in Central Asia, but for the most part the ice is shrinking dramatically around the world and it's a consequence of changing temperature and precipitation.

SI: Why are glaciers important?

JB: Glaciers are the canary in the global coal mine. They are a three-dimensional, visible manifestation of climate. They react on an hourly, daily, weekly, monthly basis to the environmental conditions around them. It's a place where you can see the effects of climate change in action. A lot of climate change that is going on around us is expressed in ways that are hard for people to grasp. Is it raining harder right now than it was before when a storm comes up the east coast of the United States? Is it drier this July in Utah because of climate change? These questions are based on measurements. You can't see it, but in ice you can see how a changing weather and climate system affects something in three dimensions. Any child understands when ice melts. You put an ice cube in the hand of a one-year-old and they understand the relationship between your body heat and the melting of that ice cube.

SI: In the past, glaciers have receded and returned. What makes the loss of glacial ice today indicative of something more permanent? JB: It's connected to a radical, extreme increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. In fact, over the past thousand years the Earth has been cooling off. If the air was responding to natural rhythms it is well understood from the temperature record from the ice sheet that we should be sliding into a new ice age. In fact, temperatures started turning around and went shooting up over the past century, particularly over the last 40 or 50 years. That is directly linked, through an enormous number of scientific studies, to greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Trift Glacier, Alps, 2006

Trift Glacier, Alps, 2011

A reciprocal effect

SI: To what extent does the loss of glacial ice have a reciprocal effect by worsening global warming?

JB: There are a lot of issues tangled up in that question. One is the loss of the Arctic sea ice. When you lose sea ice cover in the Arctic you change the reflective characteristic of a huge part of the Earth. You start absorbing more heat into the ocean water. That in turn alters the circulation of the atmosphere and changes the behavior of the weather systems of the northern hemisphere. That's a reciprocal relationship of the sort you are talking about.Â

The next thing is, if glaciers on land melt it puts water into the oceans, and sea level rises. As sea level rises you wind up with a greater capacity to absorb heat into the ocean. The more heat absorbed into the ocean makes for a more violent atmosphere. Thirdly, higher sea levels result in coastal storms where hurricanes and nor'easters [powerful storms along the upper east coast of the US and Canada] have a much greater impact on low-lying areas than they did when sea levels were just a few inches lower.

SI: At what rate is glacial ice being lost? Could we completely lose the world's glaciers?

JB: You often hear people say: "Well, if the Antarctic sheet melts it will raise sea levels 270 feet and Greenland will raise it 30 feet" or whatever. That's really not the issue. We are in the process right now of losing a huge amount of ice in the mountains of the world in Alaska, western Canada, the Alps, the Andes and the Himalayas. Those glaciers are shrinking. The glaciers will probably, in some cases, in the relatively near term, turn into just scraps of what they used to be. Here in the United States we have a national park called Glacier National Park in Montana. Â Â Â Â It's generally believed it will be ice-free in about 40 or 50 years because of glacial recession.

The big ice sheets are a different story. It would be an apocalyptic turn of events if we lose the Greenland ice sheet. If we don't have ice in Greenland we will have a greenhouse effect that will be so catastrophic we probably won't be able to live here in North America. It would be a crazy turn of events and I don't think anybody is predicting that. I am certainly not projecting that. Similarly with Antarctica. It would take apocalyptic changes in the world to de-glaciate Antarctica. But in the relatively smaller glaciers - these are not small glaciers; the glaciers of Alaska and the Alps are big glaciers - we may be losing major portions of them over the coming decades and centuries.

The world is changing

SI: Is the real issue about the melting glaciers or is that indicative of something bigger?

JB: The basic issue is not about the loss of glaciers and glacial ice. The basic issue is that the glaciers are telling us that the world around us is changing. It's a way of thinking and talking about changing weather systems, which in turn have a lot to do with natural hazards like big storms, whether hurricanes, typhoons or floods. It's a way of thinking about drought. All of these things connect with questions about food and water supply. That's the linkage of circumstances that is really key for us to be thinking about. The other big factor, which the US military is deeply worried about, is that climate change in general is something that will tend to destabilize already unstable situations in various parts of the world. All of these things are linked together and have, when you start thinking about food and water supply, about natural hazard impacts, huge consequences to a lot of people and huge costs.

SI: What role do governments have in curtailing global warming and what can they do?

JB: This is a manmade problem with manmade solutions. We know how to deal with this. The solutions are connected with economic and technological engineering and the engineering of public policy. Over the past 10 years there have been countless innovations in all of these sectors. We know what to do, but in general the financial and economic systems favor the status quo and not change. In general the political system favors the status quo and not change.

Yet, at the same time governments, especially in Europe and to some extent in China, are doing terrific things to reduce the carbon footprint of their societies. In the United States we have also done some great things. Just a year ago [2012] the Obama Administration insisted that we change the automotive fuel standards going forward. People have been trying to raise the mileage standards on cars sold in the US for a quarter century and nobody has managed to get that past the lobbying interests of Detroit. This administration did it via EPA [Environmental Protection Agency] regulations. Doubling the mileage standards will reduce the carbon footprint tremendously. That's an enormously important event.

There is a substantial majority of the American public who now understand that there is a human cause behind climate change. The polls are showing that. But in that community there is a soft underbelly that says: "Look, I understand it, but it's too late. I'm pessimistic. I don't think we can do anything about it. Everything is terrible. Everything is going to hell in a hand basket." Believe me, I can fall into that sort of thinking along with everybody else when I am having a bad day. But I don't think it is our ethical right to revert to that sort of pessimism. We owe it to the integrity of our own time and the future, to the generations to come, to stay optimistic and get ourselves in gear. We need to deal with this and stop grumbling and whining and saying, "we can't".

Educating the public

SI: Chasing Ice takes the abstract concept of climate change and makes it a pictorial reality. What effect has the film had on opening minds to the reality of climate change and its human-related causes?

JB: Certainly many people in the audiences have been converted from a previous stance of skepticism, including people who have worked for the oil and gas industry. We have also been inspiring and motivating people who are uncertain, and those who already understood this, but were dismayed. People are inspired to see that our team has sacrificed everything to tell this story.

SI: How optimistic are you about the future?

JB: I like to think we are fundamentally a smart animal that is interested in the survival of its own kind. If we can see climate change in those terms I have to stay optimistic.

For more information:Â www.extremeicesurvey.org;Â www.earthvisiontrust.org;Â www.chasingice.com;Â www.jamesbalog.com

See also:

Filed in: environment, externally authored

Leave a Reply